Indigenous video game streamers advocate for representation and education

(RNS) — Marlon Weekusk, a member of the Onion Lake Cree Nation from Saskatoon, in central Canada, is known by his icon: a howling white wolf that has held significance for him throughout his spiritual journey as a Cree. Those who know him expect conversations about tokenizing Indigenous people and representation of Cree characters in the video games he plays for fun and profit — Call of Duty and Dead by Daylight.

Weekusk is a streamer — an expert video gamer who plays for a public of mostly other avid gamers — and like other Indigenous streamers, he offers running commentary while he plays: critiques of popular games, opinions about streaming platforms like Twitch, YouTube Gaming and Facebook Gaming and stories about his culture and spirituality.

As well known as Weekusk’s identity is to his fans in the small world of Indigenous gaming, he realizes that he and his culture go almost completely unrecognized in the greater gaming world. And he is determined to change that by educating the online world while empowering other Indigenous content creators.

Weekusk said that on Indigenous reserves, sports tend to be the main pastime for kids, but “there are a lot of Indigenous youth that just don’t fit into the sports area,” he said.

Weekusk fit into the latter category. He and his siblings and cousins spent hours sitting around their TV chatting. He said it was a time to escape.

Marlon Weekusk. Courtesy photo

Today, Weekusk, a commerce student at the University of Saskatchewan who is married with two children, livestreams on his own channel, Marmar Gaming.

Weekusk occasionally features a Cree word of the day during his streams, explaining its meaning and origins. He also answers questions from viewers: What is the significance of offering tobacco? What is a powwow? What does he think about Indigenous characters in video games?

In a recent stream, Weekusk discussed the controversy surrounding the Chief Poundmaker character in the game Civilization VI. The game developers have been accused of cultural appropriation by the Poundmaker Cree Nation.

Weekusk said his goal is to show that Indigenous streamers can occupy this creative space and do it successfully. He wants to motivate and inspire other Indigenous people to take on similar roles. “Gaming has allowed me to be a positive role model for young Indigenous kids,” he said.

“I’m not prancing around in my regalia or anything like that,” said Weekusk. “I’m just sharing stories and relating to other people.”

RELATED: Native America has lessons for surviving an apocalypse, says Choctaw elder and Episcopal priest

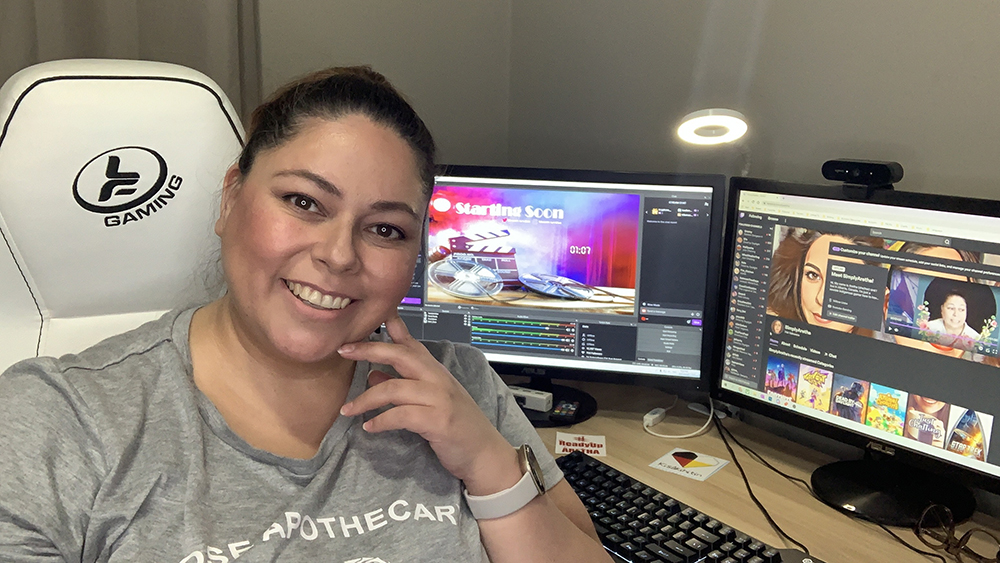

Aretha Greatrix. Courtesy photo

Other Indigenous streamers are bringing their cultures to their gaming platforms. Aretha Greatrix, who is from Kashechewan First Nation in the James Bay area of northern Ontario, has been streaming video games on her channel SimplyAretha for more than a year. Greatrix, who was born and raised in Edmonton, Alberta, is focused on fostering community among Indigenous streamers.

“We need to figure out who we are, so we can help support one another,” she said.

Last year for Native American Heritage Month in November, Greatrix invited streamers to her channel to discuss Indigenous representation in video games as they battled live. She played games such as Never Alone, which includes Indigenous communities in its plot, and Civilization VI (despite its appropriation of Chief Poundmaker).

“I try to create space for education and conversation,” said Greatrix.

Cedric Sweet. Courtesy photo

Cedric Sweet, of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, shares his identity with viewers around the world via his channel ChiefSweet, named for his great-grandfather and great-uncle, who were both chiefs of his tribe. Sweet said he draws a mix of Indigenous and non-Indigenous viewers, which leads to lots of conversation and questions about his culture.

“There are so many Indigenous cultures,” said Sweet. “And I am happy to educate and talk about mine.”

Sweet, who lives in Ada, Oklahoma, said Indigenous people have flocked to video game streaming since he began in 2016. One reason for the increase, he theorizes, is that historically lamentable internet connections on reservations have slowly gotten better in the United States and Canada.

“I see so many Native streamers in the scene now, it is really blossoming,” said Sweet. “I think right now is the best time to be a Native content creator.”

RELATED: Why Oak Flat in Arizona is a sacred space for the Apache and other Native Americans

Some, however, such as Nathan Cheechoo, from Moose Cree First Nation on Treaty 9 Territory in northern Ontario, said gamers in his home area are still waiting for better internet and more recognition. Cheechoo, who streams on his channel realswampthings, likes to advocate for the support of gaming with hopes that other Indigenous people may choose to pursue it.

Nathan Cheechoo. Courtesy photo

Cheechoo said it is up to the streaming platforms to feature Indigenous gamers more prominently on their sites. In the past, Twitch has celebrated Black History Month and Hispanic Heritage Month. In June, Indigenous History Month in Canada, and in November, Native American Heritage Month in the United States, the platform held no such events.

“It hurts because we can bring so much to platforms across the continent, yet the support for awareness is lacking,” said Cheechoo.

More support and awareness for Indigenous content creators means more opportunities, said Cheechoo. Knowing that there are companies, games, organizations and platforms that celebrate Indigenous people respectfully is important.

“This will allow for the future of Indigenous players to be proud of their identity,” he said.

On the other hand, both Cheechoo and Sweet said they do not get much hate from viewers because they are Indigenous — in part, they said, because commenters do not realize that Indigenous people still exist.

“Most people assume Indigenous people are extinct,” said Cheechoo. “So, we are definitely not a focus to those that like to criticize.”

This story has been updated to correct Aretha Greatrix’s birthplace.