An origin story for a fitness phenomenon.

In the first panel of a comic strip from 1994, a woman arrives for what appears to be a date wearing a leotard and sweatband. Her male companion wears a suit and tie and sits at a table with a white cloth draped on it. In the second panel, as she takes her seat, a sound resounds through the air: “CLANG,” reads the text, in enormous bold letters. In the third panel, the date offers his opening line: “So, how long have you had buns of steel?”

Thanks (in part) to its name, the fitness phenomenon Buns of Steel was ripe for parody in the late 1980s and early 1990s: It was spoofed on Saturday Night Live, discussed in Jay Leno’s late-night monologues, and referenced in Cathy comics. After all, butts are funny, and the idea of having a butt of steel is both alluring and a little bit ridiculous. But Buns of Steel wasn’t a joke, at least not entirely. Based on a workout regimen developed by fitness entrepreneur Greg Smithey, Buns of Steel was also a bestselling VHS exercise tape purchased all over the world by people who actually wanted to have metal-hard buns, a fact that spoke to a fundamental shift in expectations about how bodies should look and what they were for.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page.

Thank you for your support.

The butt (or at least the ass) has long been linguistically associated with hard work. Having a “fat ass” is equated with laziness and sloth, as in “Get off your fat ass and get to work.” To give a person a “kick in the ass” is to get them going, to make them go to work. To be a “hard-ass” is to be tough and uncompromising. A person can also “work their ass off,” a phrase that makes a direct connection between a small butt and diligent labor. It’s no surprise, then, that these connotations would all come together to form one of the most successful exercise programs in history during a period when commitment to gospels of entrepreneurship and self-creation in America was reaching new peaks—or that that program was invented by someone whose personal story so thoroughly embodied those principles of success.

It took me six months to track Greg Smithey down. I wrote him repeated emails at an address I found on a website he made in 2008. I scoured the phone books of Anchorage, Alaska, and Las Vegas, where I knew he had once lived. I tried to locate his representatives and his relatives. I had all but given up, assuming he had disappeared into the netherworld of the once famous, when one afternoon I received an email from Smithey saying he’d be happy to speak with me; his silence, he explained, had just been because he doesn’t regularly check his inbox.

So I gave him a call. Once he started talking, he didn’t stop for three days.

Some of the stories he told seemed dubious. He claimed that he was the “white boy” in the Wild Cherry song “Play That Funky Music” (he wasn’t). He said he trained the Commodores and Miss Alaska at his aerobics studio in Anchorage (possible, but unlikely). He told me that he is a storm chaser and has been inside eight typhoons, and described a harrowing encounter with a grizzly bear that he survived by utilizing positive thinking and a big, toothy smile. Recognizing his tendency to self-mythologize and stretch the truth, I’ve found it’s important to take anything he says with a grain of salt. There is, however, one thing that is undeniably true about Greg Smithey: He invented one of the most successful fitness phenomena of the past 40 years.

Smithey’s interest in fitness began when he discovered pole vaulting at 12 years old. He was good at it—so good that, in 1969, he attended Idaho State on a track scholarship. There he excelled, eventually jumping a very respectable 16 feet. After college, he decided he wanted to teach physical education and moved to Alaska, where he coached the Wasilla High School track team. (He claims he trained Sarah Palin.) He liked teaching and coaching, but he was a man with a bigger dream: He wanted to start his own aerobics studio and introduce a new fitness approach to the masses. After attending a life-changing motivational lecture by sound-bite optimist Zig Ziglar, Smithey quit his job, moved to Anchorage, and in 1984 opened the Anchorage Alaska Hip-Hop Aerobics Club.

It turned out to be a bumpy transition. Smithey soon found himself in a financial hole, haggling with his landlord for a break on rent and trying to figure out how to attract enough aerobics students to make the business viable. “I was looking at total failure with my exercise studio, and I got more angry and more frustrated,” he says. He decided to channel that anger into intense workouts in his aerobics classes. “Specifically, I put together a workout that just burned their butts.”

According to the website he maintains now, Smithey’s classes were filled with wild antics. He brought a cassette tape and a long leather whip (just as a prop, he reassured me), and referred to himself as Dr. Buns, Professor of Bunology, Prince of Pain, Master of Masochism, and the Bunmaster. He taught his class with the lights dimmed, a spotlight on him, music cranked. In 50 minutes, he would guide the group through at least 50 different butt-related exercises, all the while shouting, “Beautiful legs … beautiful legs … work those beautiful legs … and don’t forget to squeeze those cheeseburgers out of those thighs … and that carrot cake … and those french fries!”

Smithey says that at first there were only five or six students in his class, but the number quickly grew to over 40 repeat attendees. “They were coming because I was causing their butts to hurt so bad. And soon they started coming in and telling me all these wonderful stories about how their butts look so good and their husbands love it.” He tells me that his greatest moment of inspiration struck while talking to a group of students after class. One of them said: “Wow: Our buns feel like steel.” He recalls, “We all kind of fell silent.” They recognized genius when they heard it.

Both Greg Smithey and his bun-based aerobics class were emblematic of a change that was happening in the 1970s and ’80s in how Americans related to their bodies. Americans, influenced by the rise of neoliberalism and the ensuing individualistic zeitgeist, began to see exercise as a way to optimize themselves and physically demonstrate their work ethic. Aerobic exercise, which was first described scientifically in the late 1960s, promised women the chance to build strength and achieve a “toned” body without getting “bulky,” helping to open the world of fitness up to women for the first time even as it reinscribed traditional notions of femininity. By the time Smithey was teaching in Alaska, Jane Fonda had had tremendous success popularizing what was at first called “aerobics dance,” but both Fonda and Smithey would have a significant technological advance to thank for their ascendance.

In the early 1980s, most people didn’t have a VCR—videotapes were primarily the purview of film aficionados and pornography devotees. No one had ever made an at-home exercise video. But Stuart Karl, of Karl Home Video, saw an opportunity for wider distribution of Fonda’s workout. His wife had given him the idea after she mentioned how gyms and aerobics studios still felt unfamiliar and unwelcoming to many women. Karl reached out to Fonda and convinced her to record her routine, just to see what would happen. She agreed, and they produced the first video for $50,000. (“A spit and a prayer” is how Fonda herself describes the production.) The initial retail price was $59.95 per tape, which in turn became part of a larger investment, because most people also needed to purchase a VCR, an additional expense of hundreds of dollars.

Despite these economic hurdles, the tapes became a sensation, staying at the top of the video bestseller lists for three years and selling 17 million copies. (They are still some of the best-selling home videos of all time.) It was a phenomenon that was popular across racial lines—fashion magazines targeted at Black women, like Essence, regularly ran features on aerobics, and many aerobics videos, including Fonda’s, featured women of color following along in the background, even if the star was almost always white. As VHS tapes became cheaper, aerobics videos also became an accessible way to exercise for women who couldn’t afford pricey gym memberships. By the end of the 1980s, Fonda had not only popularized aerobics around the world; she had also become a fitness icon and laid the ground work for other instructors—like Greg Smithey—to do the same.

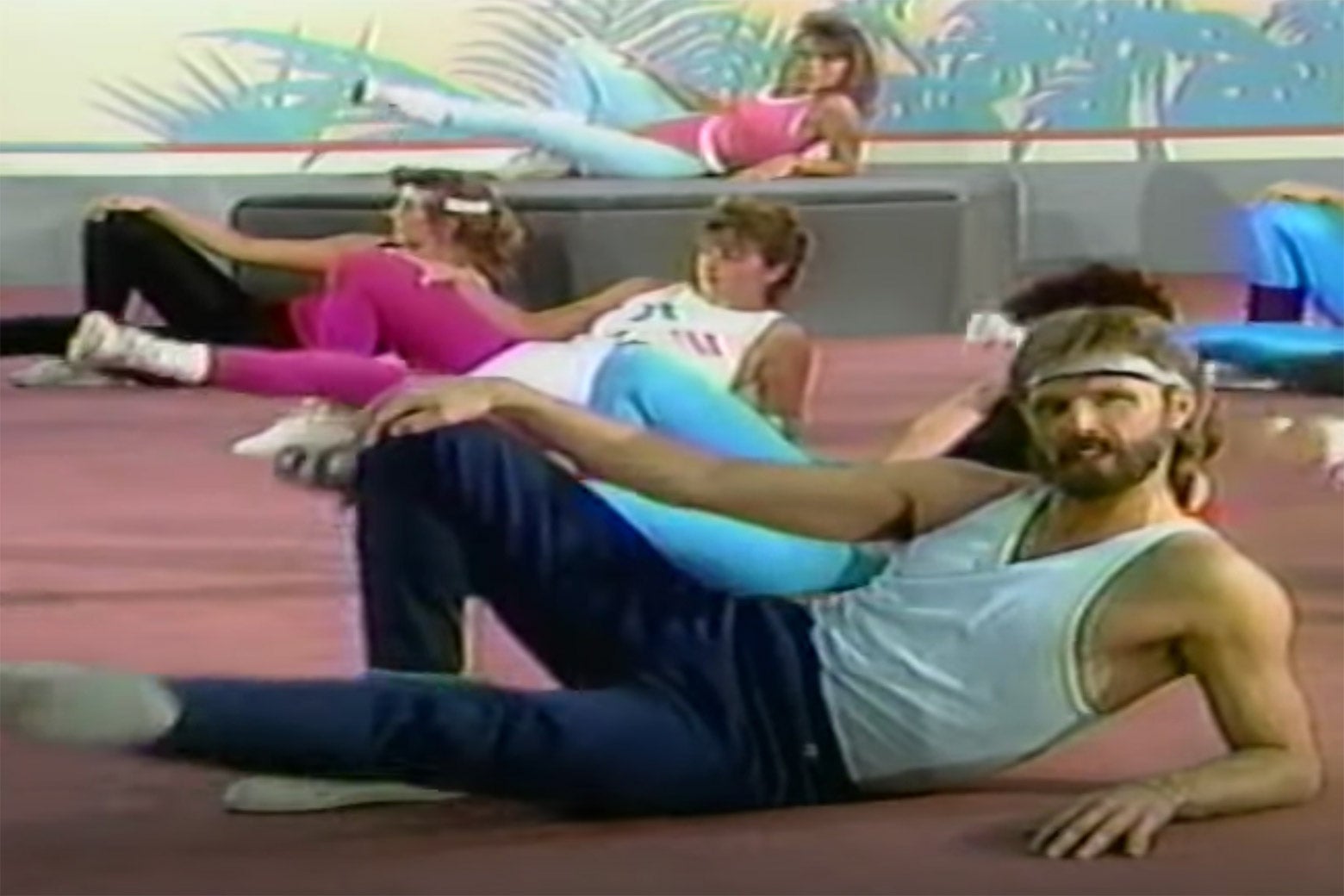

Penguin Video Store/YouTube

By 1987, Smithey was in deeper debt than ever, owing months of back rent, despite his consistently full classes. In a last-ditch attempt to turn a profit in the world of aerobics, he took a page from Jane Fonda’s book and decided to record his own instructional workout video, using the butt-burning method he had popularized in Anchorage. He acquired some rent-to-own furniture and arranged fake palm trees inside a studio that he’d painted in tropical pastels. The night before the shoot, he invited students from his class to participate, offering to pay them in pizza and soft drinks. The Original Buns of Steel was shot in two takes.

In the video (which is available on YouTube), Smithey doesn’t brandish a whip, only too-tight sweatpants, a low-cut tank top, and a sweatband. The production values are low— the lighting is garish, the picture is grainy, and the sound is tinny. The Anchorage Daily News later described it as having “an Alaska feel,” a kind way of saying it was cheaply made. The students following along in the background are occasionally out of sync or hidden behind one another. Their outfits, how- ever, are dazzling: metallic blue catsuits with bright purple leg warmers; mustard-yellow harem pants; a bright white leotard, a Floridian landscape emblazoned across the front, paired with fuchsia leggings. Smithey is encouraging, almost sweet. “You know you’ve got a great body!” he chirps to the audience. “We gotta do the other leg now!” There is no Prince of Pain here, but the workout is actually pretty hard, if at times a little boring. There are endless variations on donkey kicks and leg raises. A generic soundtrack of smooth jazz plays incessantly in the background.

At first, the videos did not catch fire. In 1988 Smithey sold only 114 tapes, almost all of them in the Anchorage area. It wasn’t enough. He was making preparations to close his studio—he could dodge his landlord no longer—and needed to make money to survive. He tried his luck at an aerobics conference in Anaheim, but he sold only one tape from his homemade booth, to Ellen DeGeneres’ assistant. (She was doing stand-up comedy at the event and wanted to use his tape as the subject of one of her jokes.)

He finally stumbled upon his lucky break—though he didn’t know it yet—when he met a video-tape distributor named Lee Spieker. Desperate for cash, Smithey sold Spieker the distribution rights to The Original Buns of Steel (though he wisely and crucially retained the copyright to the name), and eventually Spieker sold the tape to a distributor called the Maier Group. Soon after, Smithey disappeared to Guam to become what he calls “the Jimmy Buffett of PE teachers,” while the Maier Group got to work creating advertisements for their new property. (In the late 1980s, customers primarily bought tapes from print ads and catalogs; major video chains were just starting to take off.)

Even though most of the people in Smithey’s classes were women—and the target audience was female—Buns of Steel’s cover and promotional materials prominently featured a picture of Smithey and his steely buns as a promise of what you would achieve if you worked out along with the video regularly. Soon Howard Maier, president of the Maier Group, noticed that the video was selling very well in San Francisco, a spike he assumed was thanks to the title as well as what they imagined to be Smithey’s roguish appeal to gay men. In order to achieve greater mass-market interest, they decided that they needed a new strategy. They needed someone other than Smithey, someone who, like Jane Fonda, could give female consumers something to strive for. In 1988 Maier found just that in Tamilee Webb, a rising aerobics star who would become the face (and buns) of the Of Steel franchise for the next 10 years, and help make Maier and Smithey very rich.

Webb had an ideal pedigree. After earning a degree in physical education and exercise science from Chico State, she moved to San Diego and found herself in the heart of the early ’80s Southern California fitness craze. She started working at the Golden Door, one of the poshest spas in America and a celebrity hot spot. During her first week on the job, Webb trained Christie Brinkley and her mother. “Back then, it was called a fat farm,” she told me. “Now it’s the Golden Door spa and resort. People pay $10,000 a week to go there.”

For the next three years, Webb worked at several different Golden Door locations, including a couple of tours on the Golden Door’s cruise ship, where she spent her days off writing a book called Tamilee Webb’s Original Rubber Band Workout, which would become a bestseller. By 1986, she was a fitness celebrity of sorts, going on international tours, teaching at aerobics conferences, and filling up classes in San Diego. But what she really wanted was to become a star in the booming world of fitness videos.

In 1988 Howard Maier reached out to Webb, hoping she might be willing to become the face, voice, and body of Smithey’s workout regime. According to Webb, a mutual friend told Maier that he should hire her because, “one, she knows what she’s doing, and two, she’s got a butt.” As soon as Maier pitched her the project, Webb was in. “I loved training the butt and I thought: That’s a great name,” she says. As an adolescent, Webb had been teased for her “bubble butt,” but now she hoped it would make her a star.

Webb diligently rehearsed for Buns of Steel in her living room, and after a few weeks, she flew to Denver. She remembers that the set seemed cheesy and low budget, particularly in comparison to the other videos she’d starred in. The lighting was bad, the crew was sparse, there were no “backs”—the group of people following along in the background. But Webb was a professional; she put on her game face and got to work.

She stood alone on a gray carpeted platform, against a bleak white wall with glass blocks and a strangely empty shelf. The music was barely audible as she earnestly explained that she was demonstrating exercises based on “the latest research in sports physiology.” Her blond hair was arranged high on her head in a half-ponytail, and she wore coral-colored fitness bikini bot- toms with a sports bra, enormous bulky tennis shoes, and beige tights. Webb described the experience of shooting the tape as a lonely one, and it seems that way. There is something strangely melancholy about the whole thing—when you watch the tape, it looks as if she’s being held hostage in a Golden Girls prop warehouse.

Despite the awkward setup, the convergence of Tamilee Webb and the phrase “buns of steel” created a hit. “When I got my first royalty check, I was jumping up and down,” she told me. It was for about $20,000. “Then I got the next one, and it was 50 grand. And then it just kept going up.” People started recognizing her in public. At an airport, she bent over to pick something up and someone tapped her on her back and said, “Aren’t you the Buns of Steel lady?” She was recognizable based on her butt alone.

Over the next decade, Webb hosted 21 more Of Steel videos. And although her cut wasn’t huge—“Remember, I’m just the talent,” she told me—the videos sold at least 10 million copies and, according to Webb, made $17 million for the Maier Group. Greg Smithey got a significant cut, too, as the owner of the Of Steel name. “People love the name,” he says. “I made a million dollars off of three words.”

The at-home VHS workout eventually faded from mainstream prominence, thanks to the rise of gym culture, DVDs, and apps, but the legacy of Buns of Steel remains a potent reminder of the aspirational promise of fitness culture. Buns of Steel pledged to transform its practitioners into something superhuman, to turn imperfect, soft flesh to unyielding metal. The mainstream ideal had shifted yet again, from the 1940s ideal of a fertile, hearty shape to a pert, muscular, tight butt; a butt forged by thousands of reps of what Jane Fonda called “Rover’s Revenge”; a butt made of steel.

Excerpted from Butts: A Backstory by Heather Radke. Copyright © by Heather Radke. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Avid Reader Press.