why there’s no chill option for kids.

Huffing through yet another long run together, my friend and I got to talking about how unlikely it was that the two of us had, one, met at the gym, and two, were now training for a marathon. Like the many other people we’d met through kickboxing and spin classes, in running clubs and CrossFit boxes—and even in instructor certification courses—we had all strenuously avoided exercise during our youth but couldn’t get enough of it as grown-ups. “Adult-onset athleticism” is how my friend jokingly, but accurately, described our affliction.

It was the early 2000s, and our coming-of-age had coincided with a huge cultural shift in expectations and experiences of exercise. Growing up as the first generation of girls who were not just allowed, but expected, to participate in sports, and for whom “the obesity epidemic” was a nightly news staple, we weren’t expected, or even allowed, to opt out of physical exertion as our parents had—especially our mothers. Combined with new attention to the nature of stress and the power of exercise to offset it, these dynamics meant our generation felt not only opportunity but unprecedented pressure to work out. It also meant that by the time we reached adulthood, our options were more varied and inclusive than ever before. The Bay Area running group where I discovered marathoning included more middle-aged joggers than fleet-footed former athletes; high-end health clubs and community centers alike offered full schedules of cardio dance and cross-training, and the fastest-growing demographic of gymgoers was over 55. The point of exercise was no longer frantically thinning thighs or heading off a heart attack, but achieving the loftier goal of lifelong wellness.

So why, by the time we had kids ourselves, did so many of their experiences with exercise still feel as alienating as our own? With all that our generation now knows about how good fitness can feel, why does it seem like so little of that “come one, come all” spirit has made its way into the movement opportunities available to most children?

In some ways, the situation has actually gotten worse. School-based physical education continues to disappoint many kids, registering as a waste of time for the athletically inclined, and traumatic for those who are less so. Despite the broader cultural enthusiasm for exercise, PE is often on the budgetary chopping block and devalued even within the education profession as less important than academic subjects. Then you have a youth sports industry that is increasingly expensive, specialized and competitive, drawing children away from casual and community-based recreation into evermore-exclusive leagues, requiring considerable skill and money. It all adds up to a bizarre situation: an adults-only fitness culture that’s imperfect but much more inclusive than what’s available to most kids. Don’t kids also deserve a third place, where, outside of school-based PE and organized sports, they can find joy in exercising on their own terms?

It could have worked out differently. The history of exercise culture in the past century or so is primarily a story of its expansion, both in terms of what it means to work out—to improve the self, not just the body—and who is expected to do so: now, pretty much everyone. For much of that time, kids were indeed at the center of efforts to make fitness more inclusive, ennobling, and even fun. As cities grew and became more diverse, physical exercise became a way both to discipline people who were perceived as unruly and create activities for developing strength and ruggedness that reformers worried all city kids lacked. The popular concept of “romantic childhood,” which defined youth as a distinct and special life stage, meant adults readily created more opportunities for exercise geared specifically to kids. City funds went to building playgrounds, especially in working-class neighborhoods. The physical education profession gained a strong foothold in public schools, focusing squarely on improving children’s health and character through play and sport. By 1929, a majority of states had a physical education requirement, an innovation that especially created new recreational opportunities for young girls and Black kids. Adults, in contrast, mostly viewed working out in a skeptical manner: as something a circus strongman would do onstage, or that suspicious men did in dimly lit gymnasiums. Women’s advice literature increasingly focused on “reducing,” but barely mentioned exercise—which was considered unladylike—and instead favored food restriction.

During the Depression, many physical education programs in schools were eliminated. Yet youth recreation and building bodily strength as ways to help America recover became linked in the New Deal, and not only in schools. Federal funds went to building playgrounds (fun fact: Southern California’s Muscle Beach started out as one), posters by Works Progress Administration artists celebrated (free) outdoor recreation, and the popular Civilian Conservation Corps advertised the work’s ability to put muscle on skinny teenage boys as a rationale for joining up. During World War II, enlisted men became accustomed to weight training, and some brought the habit home. The prosperity the Allies had fought for, however, had a downside: Leisured suburban kids were more sedentary than prior generations—alarmingly deconditioned, according to physical fitness booster Bonnie Prudden, who warned they were unprepared to defend America if the Cold War got hot.

Nothing fires up a presidential administration like the opportunity to protect national security and child welfare, so these concerns about “soft” suburban kids gave rise to unprecedented investment and attention to kids’ physical fitness, resulting in the formation of the Presidential Council on Youth Fitness. The language of military readiness and the rigor of the curricula the PCYF promoted under Presidents Dwight Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy are mostly what the council is remembered for, especially by participants traumatized by failing the fitness test or coming in last on the mile or rope climb (or those who, on the other end of things, remember it as a lost golden age of PE). The power of such recollections can make it easy to forget that, in addition to sanitizing the seedy reputation fitness had in many quarters, the driving aim of these initiatives was to be inclusive in a way most kids’ physical activities were absolutely not.

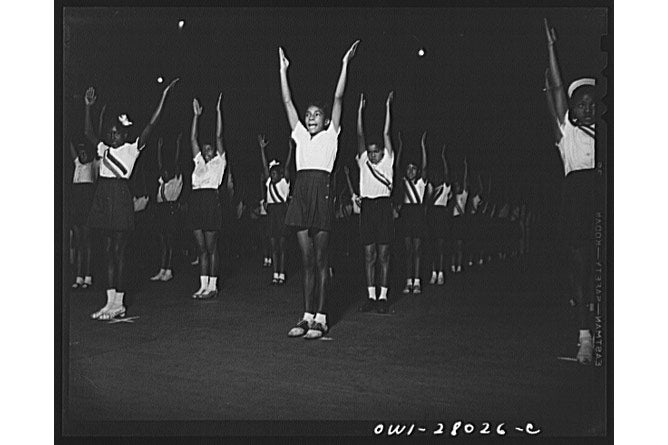

Roger Smith/Library of Congress

“No one gets cut from the squad of fitness,” announced a speaker at a 1960 PCYF conference of PE boosters and leaders, where the driving idea was not only that fitness was for everyone, but that it could and should happen anywhere and everywhere. Unlike organized sports (which necessarily selected players for skill) or physical education classes (which only occurred at school), exercise could take place just as easily in a shopping mall parking lot or on a suburban sidewalk as at a gymnasium or athletic field. In fact, one PCYF pamphlet announced that a red flag for a community was overinvestment in sports as opposed to fitness. Such emphasis on athletic excellence, fitness boosters warned, intimidated most kids out of participation and could worsen the worrisome epidemic of “spectatoritis,” in which children learned the harmful lesson, in terms of patriotism and personal health, that they belonged on the sidelines.

It was precisely this expansive vision that inspired opposition to the council’s programs. Fellow Cold Warriors criticized fitness programs that diverted dollars from the specialized science and technology curricula they deemed more important, while skeptics on the left rejected mandatory programs that extended the mood of Cold War militarism to the intimate realm of children’s bodies. Across the political spectrum, others protested that the whole scene of kids compelled by the government to exercise en masse felt fascist, or even communist. All such critics frequently mocked JFK, the country’s most prominent advocate of exercise for children and adults—he dropped the “youth” from the Presidential Council’s name to emphasize the importance of fitness for all—as a lightweight: his silly “fits of fitness,” from shirtless beach photos to challenging his brother Robert to a 50-mile hike, proved their point.

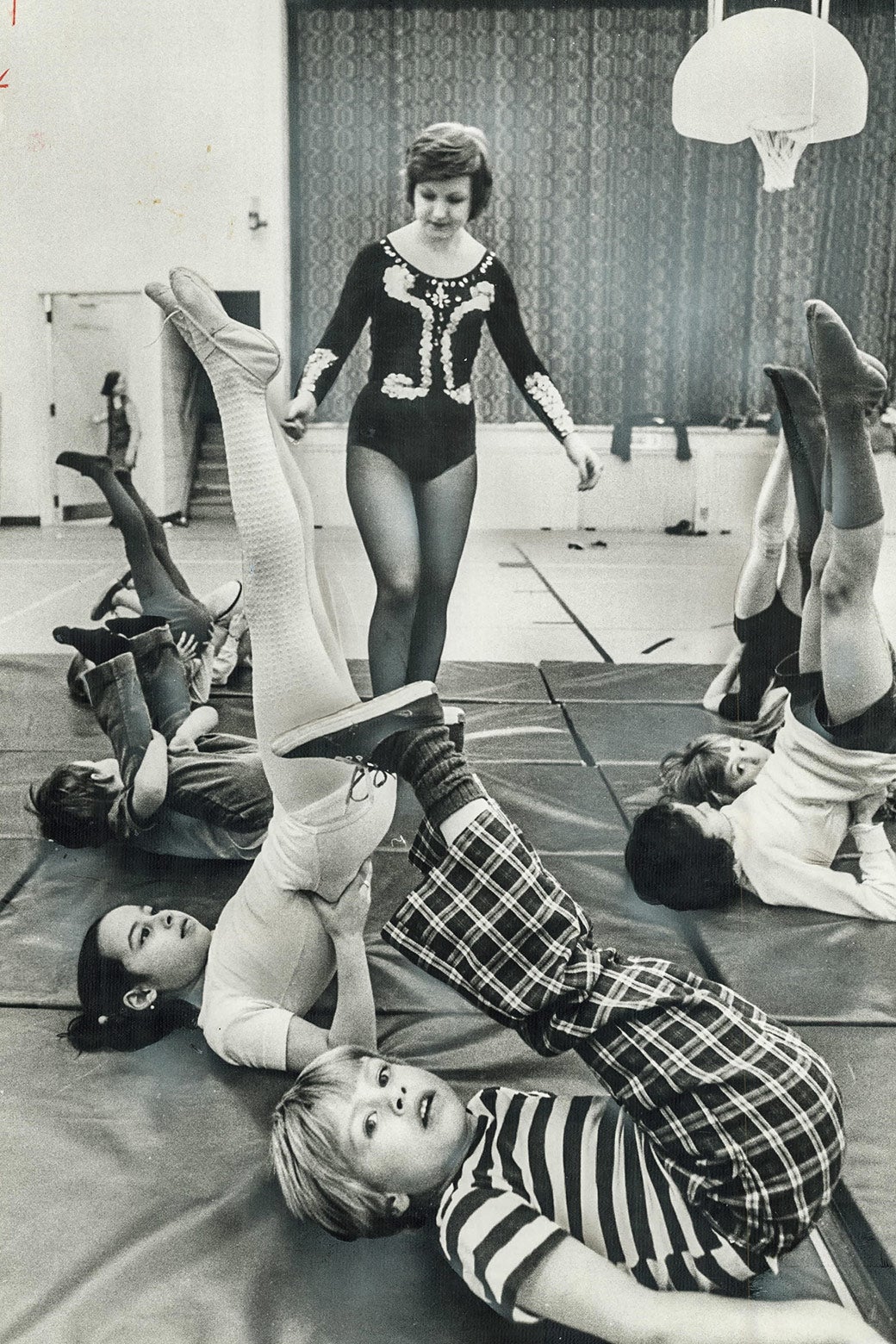

Ron Bull/Toronto Star via Getty Images

The idea that physical activity was important for all kids, however, caught on, and only shape-shifted in the ensuing decades. Title IX, which expanded girls’ rights to compete in sports, is considered the landmark achievement of the 1970s in this realm, but throuhgout the same years, progressives introduced youth programs such as yoga and martial arts that decoupled movement from individualistic competition. In the late 1970s and onward, “junior Jazzercise” and similar programs encouraged girls who might not see themselves as jocks to join their mothers in dance-aerobics classes that lacked the intimidation factor of the complex choreography and mirrors common in traditional studios. As concerns about the “obesity epidemic” and eating disorders escalated in the 1980s and 1990s, physical fitness boosters emphasized the importance of youth exercise, whether to offset a caloric diet or to channel the impulse toward bodily control into a more healthful activity than food restriction. Stress, in adults and kids, became a national fixation at the turn of the 21st century, and exercise a “wellness” practice to address it. These imperatives were classed and raced: Poor and minority kids were positioned as the problems for anti-obesity measures to solve, while their wealthy counterparts were considered at risk for anxiety and eating disorders. Across the board, however, a solution to these ills was the idea that all children can—and should—exercise.

The potential of these programs to do more than punish kids in bigger bodies or pressure them into intense exercise, however, has consistently been thwarted by resistance from many quarters. Some have argued that encouraging kids to develop their bodies is by definition a distraction from more valuable cerebral pursuits. Other critics, like intellectual Christopher Lasch, bemoaned the “degradation of sport” represented by such loosey-goosey efforts at inclusiveness. Athletic women like runner Lynda Huey, who were pushed into the physical educator track, articulated a similar complaint: Physical education in the 1960s and ’70s, especially for girls, was excessively focused on “respecting mediocrity” and not “making it about winning.” Conservative Christians later added to the onslaught by declaring that yoga in schools represented religious indoctrination.

The most obvious explanation for why this robust, inclusive vision for what kids’ exercise could be failed to pan out, while a private industry for adults has thrived, is probably the austerity policy that for decades has rolled back public programs of all kinds. Yet I was surprised to learn that, despite the lofty language of kids’ fitness boosters in the decades after World War II, such public programs not only rarely lived up to these promises of inclusivity, but, when the fitness industry boomed in the 1980s, some physical educators joined the private sector specifically because they thought it could be more inclusive than what they witnessed in school gyms and on sports fields. Fred Devito, who taught physical education and coached sports in New Jersey and California, left this stable career in the early 1980s to work at a barre fitness studio (reportedly the first man to teach in the famed Lotte Berk brownstone) because in his former career, despite his best efforts, only the already-athletic kids enthusiastically participated. The “ones who could use it the most” tended to dread experiences that “always eliminated them.” In the barre classes he began teaching, he saw women, who had felt alienated by athletics, marveling at their strengthening bodies. Carol Scott, who, as a self-described tomboy, was coached into the physical education track in college, recalled the first time she walked by an aerobics studio. The joyous, sweaty dance party, orchestrated by an instructor who seemed as overjoyed as the participants, felt viscerally different from the career she envisioned of “rolling the balls out” in the school gymnasium.

T. W. Prendiville/Edward M. Kennedy Senate files/John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

PE could have been the beneficiary of the ’80s boom in exercise, but instead it was a private fitness industry geared toward adults that profited from this expanding interest in exercise. In fact, as the industry has grown, physical education departments and public recreation facilities have largely ceased to be the spaces where innovation in fitness transpires, for children or adults. Beginning in the 1970s, universities advertised degrees and certificates in exercise science and physiology that led to private sector careers specifically separate from the physical education teacher track. In another example of such a story, Tamilee Webb, who amassed a significant fortune as the face of the popular Buns of Steel franchise, told me that thanks to the lucky timing of her birth, she was able to pursue a career in fitness: “Can you imagine? I could have been a physical education teacher.”

In the 2000s, at the height of what felt like the most exclusive moment in the private sector, when boutique fitness studios raised the price point of a workout to previously unimaginable heights, first lady Michelle Obama made the most recent and boldest public effort to promote inclusive fitness as the right of all American children. Obama’s federal initiative, named Let’s Move!, framed its mission in lofty civic ideals that echoed Kennedy’s and Eisenhower’s efforts but, instead of targeting white suburban kids, focused on Black and Latino children, statistically more likely to be obese and less able to access the expensive athletic programs or fitness businesses that were a marker of affluence. But the first lady’s endeavor was condemned by opponents on the right as nanny-state overreach and criticized by some on the left who saw it as pathologizing a structural problem, thus presenting it as an individual one. Once President Donald Trump—who personally forswore exercise and promptly changed the name of the President’s Council on Fitness, Sports and Nutrition to the President’s Council on Sports, Fitness and Nutrition—entered office, inclusive youth exercise fell off the radar as a policy priority across the political spectrum. It has not returned.

If the pandemic pressed pause on community fitness of all sorts, the ill effects of sedentariness on kids locked out of physical education, sports, and plain old play have brought more urgent attention to the need for such outlets. Some of that is happening within the physical education profession; professional association SHAPE America has committed to building a “kinder, healthier future,” a far cry from the militarism of midcentury programs. Physical educator and writer Sherri Spelic, who teaches at a private American school in Austria, conceptualizes the gym as a “social lab” that can provide “a counternarrative” to the rigidity of the rest of school. Youth versions of adult private fitness brands have also surfaced, from Crossfit to SoulCycle.

But it is a cadre of innovators and educators, working in between the public and private sectors, who are now taking up the charge to get kids inspired to exercise in a way that often remains elusive. Michele Gordon Levy told me that, as a child in the early 2000s, she “liked being active but hated PE so much” that she “faked asthma to get out of the mile [run].” When a guidance counselor recommended “a physical outlet,” her only options were dance and sports, which had strict schedules and demanded skills tightly linked to one’s place in the high school social hierarchy: “You had to be good, and that made you cool.” Levy fell in love with Tae Bo, however, and became certified as a fitness instructor at 18. Realizing that her feelings of exclusion were even more intense for her younger brothers who struggled socially, she set about designing a program to address this need. Heavily influenced by Let’s Move!, in 2010 Levy launched Adventurecize in New York City. Ten years later, amid the pandemic and in conversation with kids and parents, Levy realized “kids really needed help and it was not just obesity.” She rebranded as Zing! in 2020. Offering HIIT (high-intensity interval training) classes that combine simple movement with empowering affirmations, Levy expanded her program goals beyond physical fitness to teach “the tools to take care of yourself,” such as the awareness to recognize “when you need a run or a mindfulness break or the burst of energy of a few squats.”

Levy has since hired seven certified instructors and two full-time employees to meet the demand. Parents frustrated by lack of physical activity options for their kids first hired her to provide classes on Zoom or in person for their pandemic “pods.” Charter and private schools now hire Levy to supplant or supplement their own physical education programming. Department of Education regulations make working directly with public schools more difficult, but partnerships with the New York City Department of Transportation, public libraries, and parks mean that Zing! can offer community classes citywide. Levy’s efforts to infuse “energy, enthusiasm, and affirmations” into exercise for all—once, the sort of approach you’d mostly find at elite facilities—has been garnering her invitations to offer professional development to physical educators.

A similar ethos motivated Theresa Roden to establish I-tri, a triathlon and mentorship program for middle school girls. (Note: I served as a board member of this program from 2017–20.) Roden, who was the “last [one] picked for every softball and kickball team,” remembers “the trauma of standing there as just so horrifying” and feeling that “being athletic meant being on a sports team.” She never considered the activities she loved—walking in the woods, biking, swimming—as “real sports.” But as an adult on Eastern Long Island, she uncharacteristically registered for a triathlon in 2005, an event that conjures images of sinewy, elite athletes. Instead, Roden found that the multisport format meant few excelled at all three, and she learned from experienced runners while inspiring others in the pool and on the bike. The benefits were more significant than crossing the finish line; she began to appreciate the strength of “the big thighs I had hated all my life,” the camaraderie, and her power to cultivate her “inner voice” to stop “berating herself.”

Thrilled by this experience of empowerment through exercise, Roden lamented that, had she had this realization earlier, “life could have been so different.” When her daughter was as uninterested in athletics as she had been, Roden—especially inspired by growing data that shows sports participation is linked to less drug use as well as better social adjustment and academic performance—founded I-tri with eight initial participants. Since its inception, she’s defined I-tri in contrast with physical education, which “is designed, after all, by people who probably loved being competitive and picking the teams so much they want to make it their career.” Instead, I-tri, which now serves more than 700 predominantly Latina girls through grants and fundraising, teaches that anyone can train for a triathlon and that collaboration around an athletic commitment can provide a strong foundation for confronting issues of mental health, food insecurity, identity, and educational attainment. I-tri works directly with schools in order to ease the logistics of participation, but operates as an extracurricular activity. Yet one goal of Roden’s, who has an education degree, is to shift athletic culture within schools to “instill the lifelong love of being active and appreciating what your body can do.” One of the program’s first graduates plans to become a PE teacher, Roden recounted, “and that is where the change comes.”

“Every program loves to say youth sports are so great because they teach kids to be leaders and be creative,” Macky Bergman, who founded the youth basketball nonprofit Steady Buckets in 2010, told me. “But then all the power and the decision-making is always with the adults in charge.” Bergman’s inspiration hardly came from youthful alienation from athletics; he was a varsity college basketball player. But he saw another problem: Conventional school sports and PE weren’t imparting high-quality skills training, and the athletes who could afford it were self-selecting into elite, competitive travel programs at ever-younger ages. Aside from the high price tags, these quasi-professional programs were organized entirely by adults. In contrast with the casual pickup games of his youth, parents and semiprofessional coaches were managing and directing everything from a young age, often sucking kids’ joy—and certainly their agency—out of the experience. Bergman would see photos of championship-winning teams in which, he said, “the parents are smiling, but all the kids are miserable.” Funded by donors, Steady Buckets offers free basketball instruction to nearly 2,000 participants who hail from 154 of 172 New York City ZIP codes, and is staffed mostly by youth coaches trained in its Young Leaders program. This emphasis on developing coaches along with athletic skills is what allows the program to engage kids of varying abilities as they grow up, since “the best coaches aren’t always the best players, and vice versa,” Bergman told me. It’s not always easy, he said, but when things go well, “it’s like basketball utopia.”

If not quite utopia, the spaces that Levy, Roden, and Bergman are trying to create, and that their predecessors like Prudden, Kennedy, and Obama also envisioned—where exercise is intertwined with building community and character, rather than only physical strength and athletic skill—are amazing where they exist. And kids should not have to wait until adulthood to enjoy them.

Update, Sept. 26, 2022: This piece has been updated to remove an early-20th-century photo of a physical education class at Carlisle Indian School.