An interview with the inventor, Don Rawitsch.

Fifty years ago this winter, a young student teacher by the name of Don Rawitsch introduced his eighth grade American history class to a computer game on westward expansion that he had developed along with his colleagues Bill Heinemann and Paul Dillenberger. The game, called The Oregon Trail, would go on to sell over 65 million copies, many of them to educational institutions, making it one of the bestselling games of all time, right up there with Super Mario Bros. and Tetris. But when I talked to Rawitsch recently, he said that when he first came up with the idea, making money was the furthest thing from his mind.

“Back in 1971, there was a lot of activity going on in the world of schools to upgrade curriculum and come up with innovative methods of teaching,” Rawitsch said. Inspired by his teachers at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota, Rawitsch decided to pursue new types of pedagogy for his student teacher classes at Jordan Junior High School in Minneapolis. “I was excited and maybe a little naïve,” Rawitsch recalled. “I really wanted to do some things in the classroom that the students were not necessarily used to.” Before developing The Oregon Trail, Rawitsch had attended class with another instructor dressed like Lewis and Clark and attempted to speak and answer questions as the famous explorers. For classes on the Civil War, he tried to recount battles for students through songs that he wrote and performed in class with his guitar. Rawitsch also worked with a track coach at Jordan Junior High on a mock trial assignment for students that began with someone being shot with a starter pistol—the type of innovative pedagogy that most definitely would get you fired today.

For his classes on westward expansion, Rawitsch decided to try something a little safer: a board game with a big map and some toy covered wagons. “In my college work,” Rawitsch said, “I had seen some examples of educational games that were in a box game format … [and] I was kind of fascinated by the idea that this would be something you do in a classroom that would probably be much more interesting to students than just reading about history.” Rawitsch began work on this board game in the apartment he shared with fellow Carleton College student teachers, Paul Dillenberger and Bill Heinemann, who both taught math and dabbled in computer programming. They suggested Rawitsch ditch the paper-and-pencil approach; they would help him convert this game into a computer program that could run on his school’s teletype, a monitorless machine connected via the phone line to a mainframe computer in downtown Minneapolis. The two math teachers sometimes used the machine in their own classrooms; when they weren’t using it, the teletype lived in the school’s janitorial closet.

Rawitsch introduced the resulting game, which he called Oregon at the time, to his class on Friday, Dec. 3, 1971. “We spent a week on Oregon Trail,” Rawitsch remembers, “and so [the students] had four or five days to try it out. And they were … compared to the usual nonexcitement of reading about history … extremely excited to do this and fascinated by the computer.” For many of Rawitsch’s students, this moment not only represented their first time playing a digital game, but also their first time using a computer. Rawitsch believes that, out of the students he taught, “probably 90 percent of them had never had a chance to take a turn on the one computer” at the school.

Because of this fact, Rawitsch collected his class into groups of five to play the game together. This setup gave everyone an opportunity with the computer, allowed the students to troubleshoot the machine collectively, and mimicked the family dynamic of traveling along the historic Oregon Trail. “The kids took their turns,” Rawitsch said, “each small group … gathered around the teletype terminal. And, of course, they were all anxious to read the output that was being printed by [the machine].”

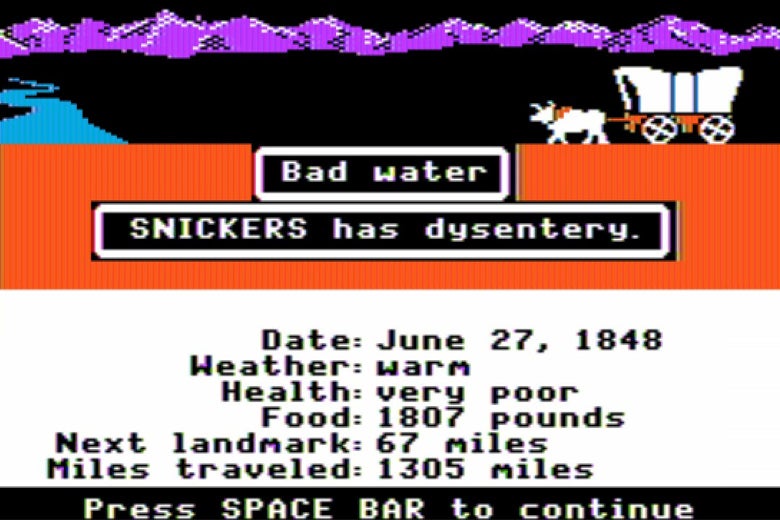

This initial version of The Oregon Trail was designed to supplement student knowledge of westward expansion, but it also tested their abilities with resource management, teamwork, and typing. For example, in order to hunt for food, students had to accurately and quickly type either “BANG” or “POW” into the machine, or risk missing their target. “All five kids wanted to type [at the same time], and they wanted to get that done very quickly,” Rawitsch said, “and they soon discovered that that wasn’t the most efficient way to go about this because, invariably, they would get typos.” During their week on The Oregon Trail, each student group got at least one full playthrough finished, with some successfully reaching Oregon. But their enthusiasm for the game didn’t stop there. “There were times when certain groups finished their trip before the bell rang,” Rawitsch remembers, “and so kids … started over for as long as they could. … Once I started using this [game] in my classes, I got students coming in after school and lunch period and so forth, just because they wanted to try it many times over.”

This is the moment in the biopic when the creators realize they are sitting on a gold mine, and they convert The Oregon Trail into a commercial product. But instead, at the end of that fall semester, Rawitsch, Heinemann, and Dillenberger—those humble and respectful student teachers—printed out the game’s source code from the teletype machine and deleted The Oregon Trail from the school district’s mainframe. The game that would go on to sell 65 million copies would spend the next three years in a folder in Rawitsch’s bedroom desk. It was, after all, a one-off classroom exercise for an eighth grade history class, taught by a student teacher.

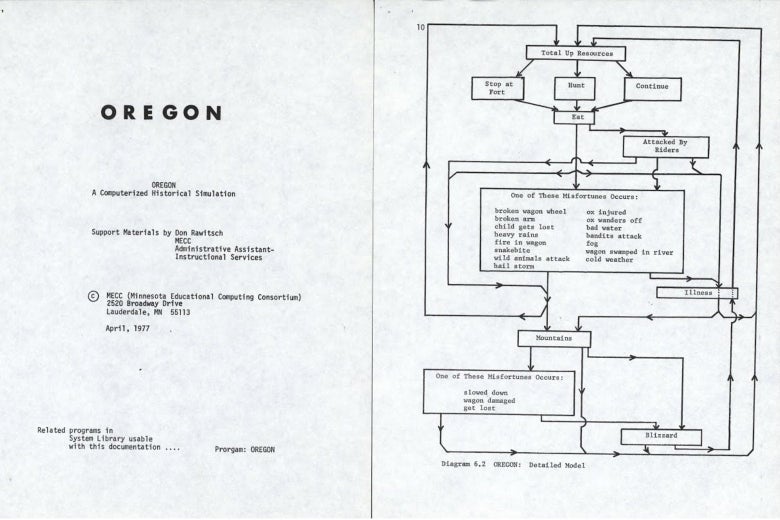

How, then, did this game go from Rawitsch’s desk to millions of classroom computers around the country? “I was hired by MECC [Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium] in October 1974,” Rawitsch said, “and we had a share library where people could submit programs they had written, and then the staff would decide if they were worthwhile putting in the library [for students across the state]. … So over Thanksgiving weekend I had a cold and I had nothing else to do. … I decided to bring a portable [teletype] terminal back to the house. And from the kitchen phone, I connected to the MECC computer and typed in line by line the code on the [Oregon Trail] printout.” After Thanksgiving, Rawitsch “started showing it to the staff and they were enthusiastic. So, then [Oregon Trail] became available to Minnesota schools that were using that mainframe computer, and over the next couple of years it became extremely popular.”

The Strong National Museum of Play, Rochester, New York

So this is the moment when the financial windfall comes, right? Overtime pay for working on Thanksgiving, at least? “No,” Rawitsch said, laughing, “there was just no cognizance of that. I considered myself to be an educator.” As The Oregon Trail grew in popularity in Minnesota, Rawitsch the educator decided to share the source code for the game in an article for the national magazine Creative Computing in 1978. “I think the fact that was in 1978,” Rawitsch argues, “indicates that as late as then there was still no understanding that there was soon to be a software market. A big one. … So should [I] write an article about The Oregon Trail … and then give you all the code so that you can type it into something else? Yeah, why not!” Rawitsch continued: “When you’re an educator, you’re encouraged to write and publish. … Paul and Bill and I, when you get right down to it, we were teachers. We have the teacher mentality. And so, [to get] rich off this would have been nice, but not as important as having donated something to the world of education.”

History-themed digital games, of course, are now big business, with titles such as Assassin’s Creed Valhalla, Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War, and Red Dead Redemption 2 representing some of the most profitable games in recent years. But in that mix of ahistorical action and bombast, there is still space for educators to get involved. Assassin’s Creed Discovery Tour: Viking Age features the work of dozens of scholars from around the world. Charles Games’ adventures Attentat 1942 and Svoboda 1945 rely on instructor advice and public funding. The first-person narrative game Blackhaven was developed by a history Ph.D. This year, the academic journal of record, the American Historical Review, started to include video game articles and reviews. And the latest version of Oregon Trail includes input from three Indigenous historians, to consider westward expansion from a Native perspective.

For Don Rawitsch, who would go on to work for MECC for almost 20 years, this latest iteration of Oregon Trail is most welcome. For an educator who gave away his greatest lesson plan, the goal wasn’t to be authoritative, but to create a platform that could be used by others and iterated on—with better technology but also better history.